The Road To Serverless: Storage Engine

Last modification on

Author: Ed Huang (i@huangdx.net), CTO@PingCAP

The Road to Serverless:

In the previous article, we introduced the “Why” behind TiDB Serverless and the goals we hoped to achieve. Looking back now, in the process of building TiDB Serverless, I believe the biggest architectural change has been in the storage engine. The storage engine has been the key contributor to reducing overall usage costs.

Another reason why emphasize the storage engine,is because if the compute layer is well abstracted, it can achieve a stateless state (as seen in TiDB’s SQL layer), and the elastic scalability of stateless systems is relatively easy to achieve. The real challenge lies in the storage layer.

In the traditional database context, when we talk about storage engines, we typically think of LSM-Tree, B-Tree, Bitcask, and so on, these storage engines are local, so, for a distributed database, a layer of sharding logic is needed on top of the local storage engine to determine the data distribution across different physical nodes. However, in the cloud, especially when building a serverless storage service, the physical distribution of data is no longer critical because S3 (object store, which includes, but is not limited to, AWS S3) has already addressed scalability and distributed availability remarkably well (and there are also high-quality open-source object storage implementations in the community, such as MinIO). If we consider a new ‘storage engine’ built on top of S3 as a whole, we can see that the entire design logic of the distributed database is significantly simplified.

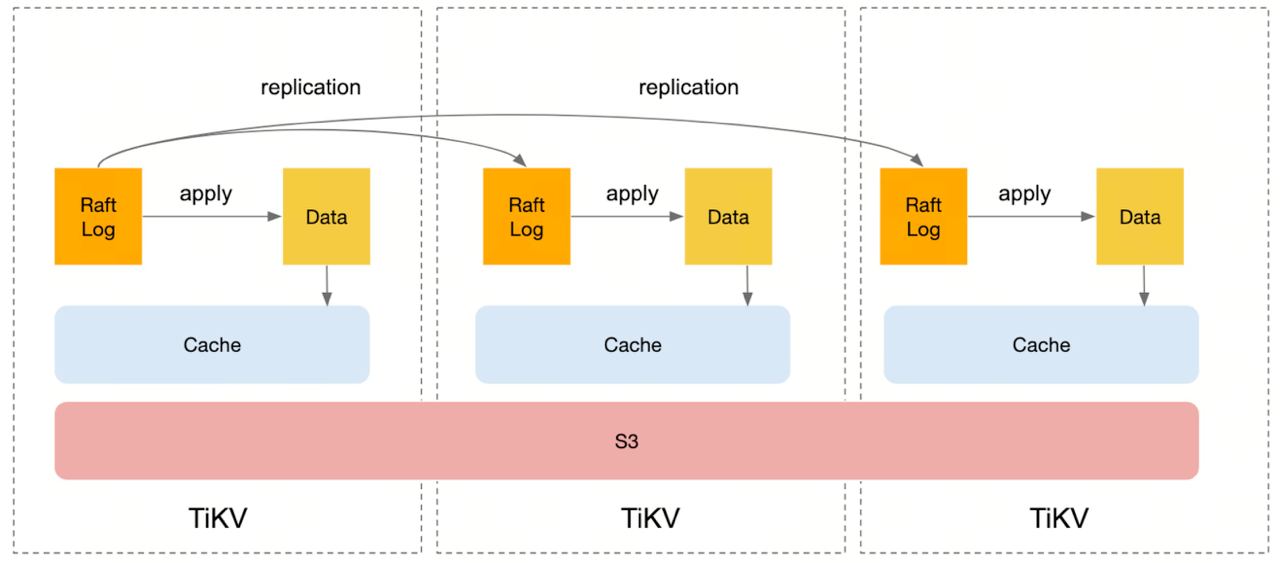

But S3 has a limitation in terms of the I/O latency for small I/O, so it cannot be directly used in the primary read-write path of OLTP workloads. Therefore, for writes, data still needs to be written to local disks. However, as long as we ensure successful log writes, implementing a distributed, low-latency, and highly available log storage is much simpler compared to building a complete storage engine (because it’s just append-only). Therefore, log replication still needs to be handled separately, and options like Raft or Multi-Paxos can be chosen as RSM (Replicated State Machine) algorithms, or one can even rely on EBS for a more simplified approach. As for read requests, if we want extremely low latency (<10ms), we primarily rely on in-memory caching. So the optimization direction is focused on implementing several levels of caching and deciding whether to use local disks, and whether to cache at the page or row level. Furthermore, in a distributed environment, one advantage is that since data can be logically partitioned, the cache can also be distributed across multiple machines.

Here are the design goals for the new storage engine for TiDB Serverless:

Support Read-Write Separation

For OLTP workloads, reads typically outnumber writes. Additionally, an implicit assumption is that the demand for strong consistency reads (read-after-write) may only represent a small portion of all read requests. Most read scenarios can tolerate an inconsistent gap of around 100ms. However, writes consume more hardware resources (excluding cache misses). In a single-node environment, achieving a perfect balance is challenging because of the limited resources available for reads, writes, and compactions. However, in a cloud environment, reads and writes can be separated. The local data can be replicated to multiple peers using the Raft protocol, while log data is continuously and asynchronously synchronized to S3 in the background (with remote compact nodes performing compactions). For users requiring strong consistency reads, they can read from the Raft leader. If there is no requirement for strong consistency, reads can be performed on other peer nodes (considering that even with asynchronous log replication, the gap is not excessively long, as it is based on Raft). Even if strong consistency reads need to be implemented on non-leader peers, it can be easily achieved by requesting the latest log index from the leader and waiting for the log corresponding to that index to be synchronized locally. Newly added read nodes only need to load the snapshot from S3, perform cache warming, and then provide services. Additionally, the additional benefit of transferring snapshot data through S3 is that intra-region traffic across availability zones is not counted. Moreover, for analytical queries in HTAP scenarios, since the data is already on S3, and most analysis scenarios only require read-committed isolation level and stale reads, they can be handled using the aforementioned read nodes. Furthermore, reverse data backfilling for ETL can also be accomplished through S3.

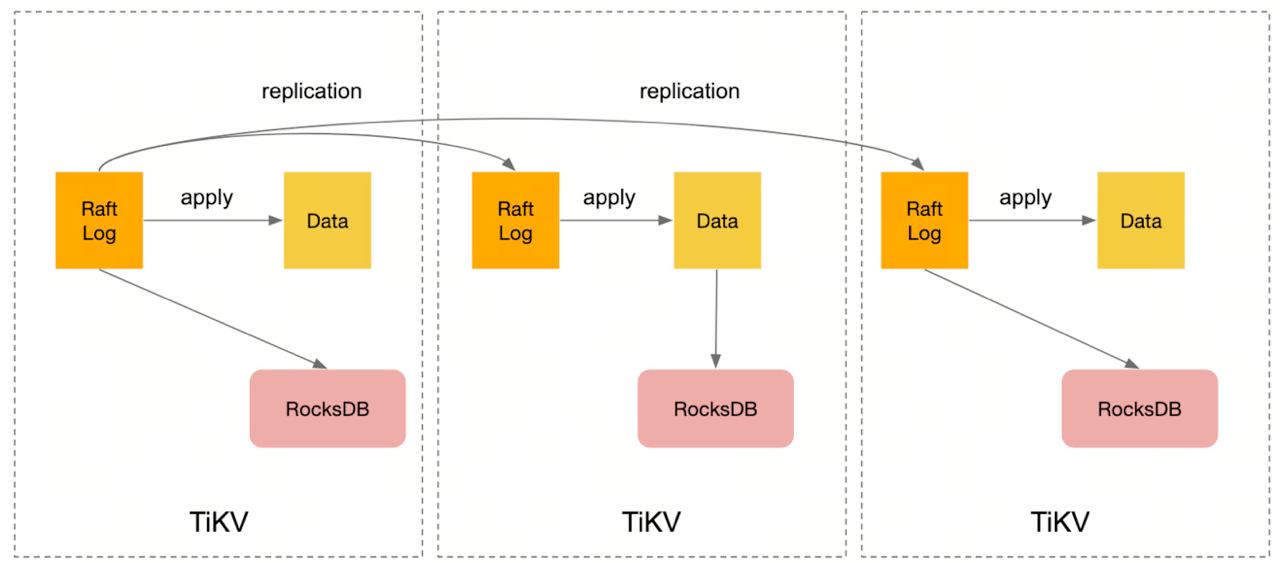

(Before)

(Before)

(After)

(After)Support Hot-Cold Separation

For OLTP scenarios, we observe that although the total data volume can be substantial (we often encounter OLTP businesses with hundreds of TB), there is often a distinction between hot and cold data. For cold data, providing an “acceptable” experience is sufficient, and the tolerance for read-write latency on cold data is generally higher. However, as mentioned earlier, we often cannot strictly classify data as hot or cold. Nonetheless, we want to separate cold data onto cheaper hardware resources while preserving the accessibility of hot data. In Serverless TiDB, it is natural to store cold data only on S3 because the hierarchical storage design naturally retains hot data on local disks and in memory, with the coldest data residing on S3. One drawback of this design is the increased latency during cold data cache warming due to loading from S3. However, as mentioned before, in practical scenarios, this latency is usually tolerable. If the user experience in this scenario needs improvement, the addition of a cache layer can easily address it.

Support Rapid Elastic Scalability (both Scale-out/in) and Scale-to-Zero

When discussing hot-cold separation, there are two implicit topics that have not been covered:

- How to handle write request hotspots?

- How to quickly detect hotspots?

To answer these questions, we need to discuss data sharding, request routing, and data scheduling. These three topics are also key to supporting elastic scalability. Let’s start with data sharding. In traditional shared-nothing architectures, logical and physical data shards are one-to-one. For example, in TiKV, a region corresponds to a segment of physical data in a TiKV node. A more familiar example is MySQL sharding, where each shard is a specific MySQL instance. However, in the cloud, if there is a cloud-native storage engine, we no longer need to be concerned about the physical distribution of data. Nevertheless, logical sharding remains important as it involves the allocation of compute resources (including caching). The challenge with past shared-nothing distributed databases was that adjusting shards required data movement and migration, such as rebalancing after adding/removing storage nodes. This process was prone to issues because any physical data movement complicated the task of ensuring consistency and high availability. TiKV’s Multi-Raft has devoted significant effort to this aspect. However, for a storage engine based on S3, data movement between shards is merely a modification of metadata, and the so-called physical movement is primarily a caching warm-up issue on the new node.

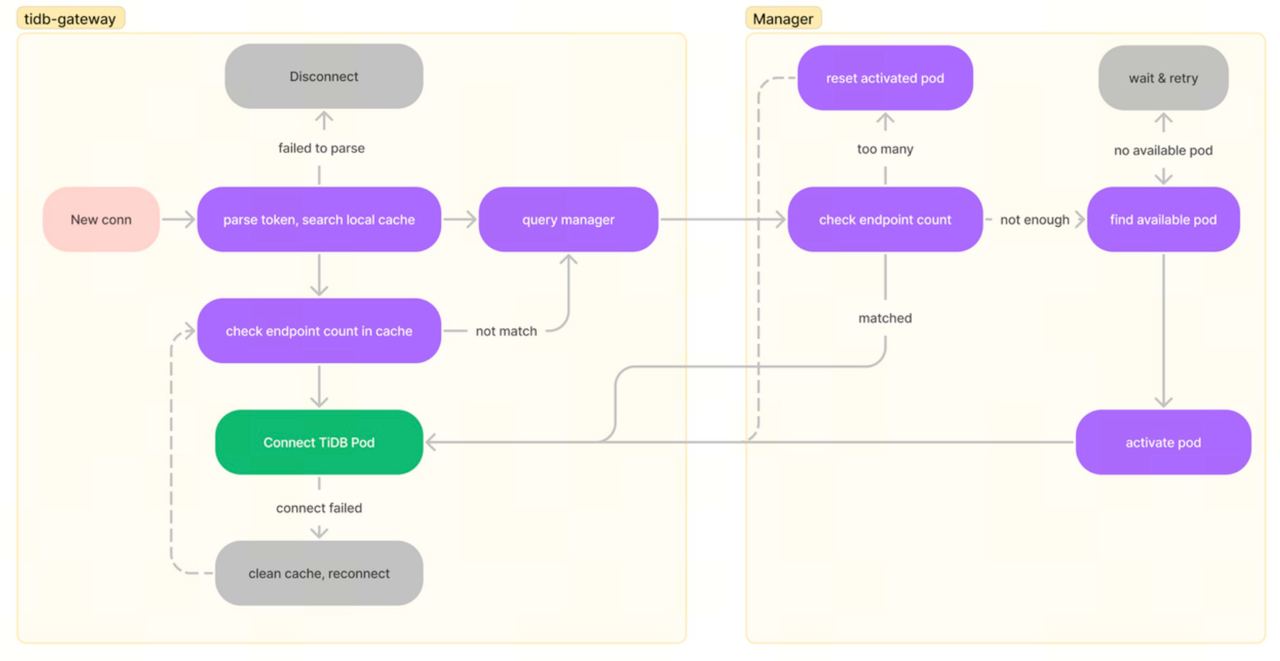

Having logical data sharding implies the need for a corresponding request routing layer, which routes requests to specific machines based on rules. I still believe that, just like TiKV, using KV ranges as a sharding method is effective. It’s similar to using a dictionary where you can precisely locate a word based on lexicographic order. In TiDB Serverless, we retain the KV sharding and logical routing, but add a proxy layer on top of the original TiDB to manage sessions for different tenants. Let’s call it the gateway. The gateway is crucial for tenant isolation and traffic awareness (mentioned later). When the gateway detects a connection from a tenant, it retrieves an idle tidb-server pod from a cached compute resource pool (the tidb-server container pool) to handle the client’s requests. The connection is automatically returned to the pool when it is disconnected or times out after a certain period. This design is highly effective for rapid scaling of compute resources, and the stateless design of tidb-server simplifies the implementation of this capability in TiDB Serverless (thank you, past self!). Moreover, when the gateway detects the emergence of hotspots, it can quickly scale out by adding more compute resources. The expansion of compute resources is straightforward to understand, and the expansion of the storage layer is also simple—just modify the metadata and mount the remote storage on the new node, then pre-warm the cache.

Cost Efficiency

In the cloud, all resources come at a cost, and pricing for different services can vary significantly. A simple comparison of the pricing for S3, RDS, and DynamoDB reveals substantial differences. Moreover, compared to service fees and storage costs, it is easy to overlook the cost of data transfer (sometimes you may find that traffic expenses outweigh storage costs on your bill). There are several key strategies for cost savings:

- Utilize S3 for cross-Availability Zone (AZ) data movement and sharing to reduce cross-AZ data transfer costs.

- Leverage Spot Instances for offline tasks. Offline tasks are defined as stateless (persisted in S3) and reentrant. Typical offline tasks include LSM-Tree compaction or backup restoration.

Being able to reuse the majority of the original TiDB code.

TiKV has a good abstraction for the storage engine, so the main modifications were focused on the replacement of RocksDB. The logic related to log replication and range sharding can be mostly reused. As for the SQL engine and distributed transaction parts, they were already loosely coupled with the storage layer, so the main modifications are the support of multi-tenant. This is also why we were able to launch the product within approximately a year with a small team (core dev <20ppl).

So, this is the main design goals and technical choices for the cloud storage engine in TiDB Serverless. In the design of TiDB Serverless for multi-tenancy, we have also utilized many features of the storage layer. Therefore, in the next article, I will introduce the implementation of multi-tenancy.