Vibe Engineering in 2026.1

Last modification on

Ed Huang | CTO/Co-founder, PingCAP TiDB | h@pingcap.com

After I introduced OpenCode in my previous article, I received a lot of attention and feedback from friends. Over the past few weeks, I’ve also gained more hands-on experience with Vibe Engineering, so today I want to summarize again.

You may notice that I deliberately avoid using the term “Vibe Coding.” That’s because the focus at this point is no longer just on code, but on things at a higher level. Also, I’ll try to keep the “AI content” in this article under 5%, so feel free to read it without pressure.

As a quick update: my TiDB PostgreSQL rewrite project I mentioned last time is no longer a toy. A few days ago, while traveling for work on a long flight with no internet, I did a careful review of the code. There are some rough edges, but overall the quality is already very high. In my view, it’s close to production-level Rust code, which is very different from what I used to consider an “early prototype.”

By the way, choosing Rust from day one was absolutely the right decision. Rust’s rigor makes it easier for AI to write infrastructure code that is much closer to being bug-free. In contrast, another project of mine, agfs, uses Python for its shell and built-in scripting language (ascript). As the project grew, maintainability dropped sharply, and at that point rewriting it became extremely difficult, so we could only refactor slowly and painfully. So now that it’s already 2026, if you’re starting a new backend infrastructure project, Rust should be your first choice.

After validating things to this point, I also invited a few of the top “vibe coders” on my team to join the project. The idea is to see how far and how fast we can push it using a 100% AI-native development model. No matter what, I’m very curious to see the result. It should be interesting.

Below are some of my recent thoughts.

Everything we think we know about Vibe Engineering will be seriously outdated within one month

This is not an exaggeration. Even this article—if you’re reading it in February 2026—there’s a good chance much of what I’m discussing here is already outdated. This field is moving extremely fast. Many things that are SOTA today may be obsolete next month.

What’s also interesting is that many well-known figures who used to dismiss Vibe Coding—people like DHH, Linus, Antirez—started changing their tone around December 2025. That feels very normal to me. Starting last December, AI programming tools and top-tier models made a sudden, leap-like improvement. Their ability to understand complex tasks and large projects, as well as their code correctness, increased dramatically.

This progress mainly comes from two areas.

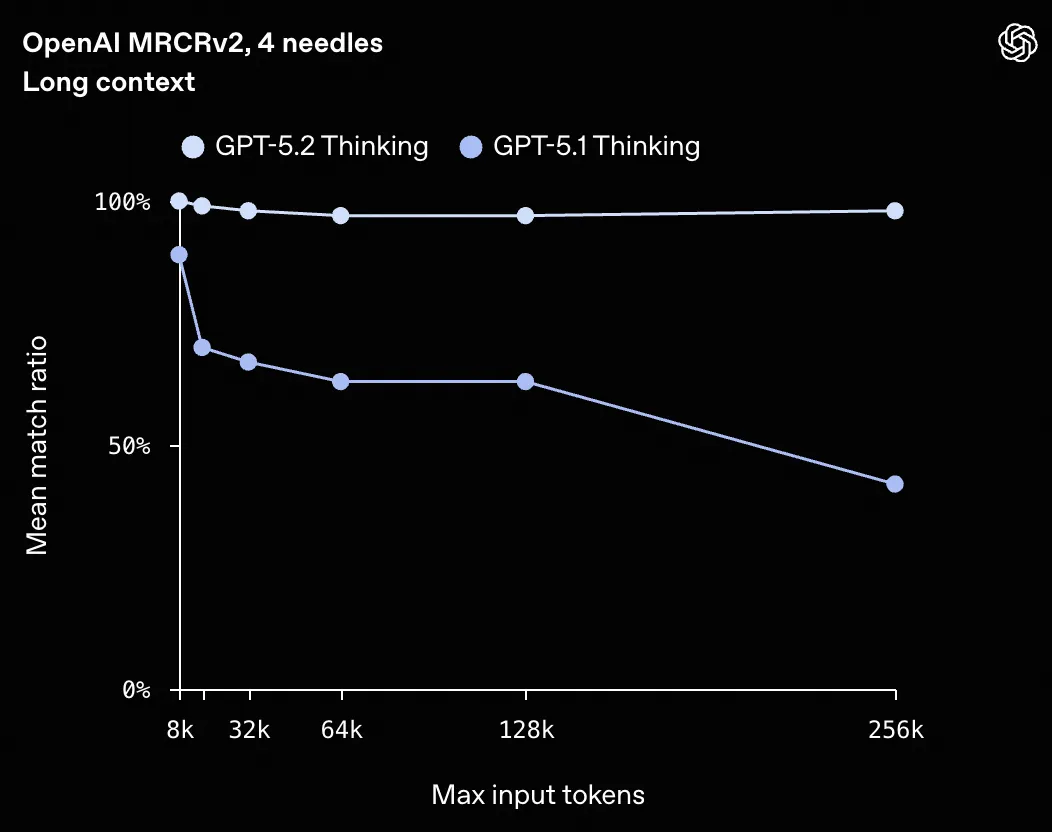

First, top models now support very long context windows (>256K), and more importantly, their recall of key information has improved dramatically.

For example, the chart above shows the long-context recall performance of GPT-5.2 compared to GPT-5.1, and the difference is very clear. For agent coding scenarios, you usually need multi-round reasoning plus long context (because you have to include more code and intermediate reasoning) to maintain a correct global view. And having the right global view is a decisive factor for complex projects.

In this kind of scenario, you can do a simple calculation. If a model like GPT-5.1 has a recall rate of 50% per round, after about three rounds the effective correct recall drops to 12.5%. GPT-5.2, on the other hand, can still maintain over 70%.

The second improvement is that context engineering practices in mainstream Vibe Coding tools—such as Claude Code, Codex, and OpenCode—have become much more mature. From user experience to best practices, things are visibly getting better. Examples include Bash usage, sub-agents, and so on. More and more senior engineers are using these tools heavily and sharing their experience, which creates a data flywheel for further evolution. And since AI itself is deeply involved in developing these tools, the iteration speed will only increase.

This wasn’t really some sudden magic breakthrough in December. Things had been improving for months before that, but AI still couldn’t operate without frequent human intervention. Around that time, the quality of mainstream coding agents crossed a critical threshold: running long agentic loops with zero human intervention became possible.

Hire the best (model), otherwise you’re wasting your life

From my perspective, all of the progress mentioned above only really exists in the very top closed-source models. I’ve heard many friends tell me, “AI programming still feels kind of dumb. It’s not nearly as smart as you describe.” My first question back is usually: are you just using a $20-per-month entry-level model? If so, try using a $200+ Pro Max tier for a while. You might be surprised.

In my opinion, even non–top-tier mainstream models are already more than sufficient as chatbots for most people’s short-context daily tasks. Even GPT-4, when talking to you about life philosophy, can already leave you pretty stunned.

As humans, our intuition—or simple CRUD demos—can no longer evaluate the intelligence gap between these models. But in complex project development, that gap becomes extremely obvious.

Based on my own experience, there are basically only two models that can currently be used for large infrastructure projects (databases, operating systems, compilers, etc.): GPT-5.2 (xhigh) and Opus 4.5, with Gemini 3 Pro being maybe “half” a contender.

About a month ago, I was mainly using opencode + oh-my-opencode + Opus 4.5. But over the last two weeks, I’ve shifted to a Codex + GPT-5.2 combination. Below are some personal impressions of these models—their “personality” and style—strictly from my experience in backend infrastructure development.

Opus 4.5 is very fast and very talkative. Because Sonnet 4 had serious reward-hacking issues—for example, when it couldn’t fix a bug, it would secretly cheat by constructing fake tests to make things pass—I avoided the Sonnet series for complex tasks for a long time. Opus 4.5 fixes this problem well. Even when it’s clearly stuck and can’t solve an issue after many attempts, it doesn’t cheat. That made me much more comfortable using it.

The downside of Opus is that it doesn’t spend enough time on reasoning and investigation. It jumps into implementation too quickly. When it later realizes something is wrong, it has to backtrack to re-check assumptions and do more research. This behavior is what led to tricks like ralph-loop—for example, running the same prompt again via a stop hook after Claude Code finishes, forcing it to go through the entire process again and gradually converge on a better result.

In contrast, GPT-5.2 feels much more cautious and less talkative. My initial experience with Codex wasn’t great, because it felt slow. That’s mainly because I often use its xhigh reasoning mode. Before writing any code, it spends a long time browsing files and documentation, doing a lot of preparation. The Codex client also doesn’t tell you its plan or how long it will take, so the process feels especially long. For complex tasks, the initial investigation phase alone can take one or two hours.

However, after that long thinking phase, the results are usually better—especially once a project’s overall structure has stabilized. Codex tends to be more thorough, with fewer bugs and better overall stability.

As for the third top model, Gemini 3 Pro: I know its multimodal capabilities are very attractive, but for complex coding tasks, at least in my personal experience, it’s not as strong as Opus 4.5 or GPT-5.2. That said, it’s clearly optimized for fast frontend demos and prototypes, and its Playground mode makes it very convenient when you want to quickly build something flashy or visual.

There’s also a counterintuitive point here. In the past, we often said that Vibe Coding was only good for simple things—small demos or CRUD projects. You see many KOLs online doing exactly that. On the other hand, people generally believed that AI couldn’t handle core backend infrastructure code.

I used to think that way too. But since last December, that conclusion probably needs to be revised. The reason is that infrastructure code is usually crafted over a long time by top engineers. It has clear abstractions, good tests, and is often quite refined after multiple refactors. When AI has enough context space, better reasoning, more mature agentic loops, and efficient tool usage, infrastructure development and maintenance actually become one of the scenarios that best leverage the intelligence of top models.

In real work, I often let multiple agents collaborate or use complex workflows to orchestrate them. I don’t rely on a single model to do everything. I’ll share more concrete examples from my own practice later.

When do humans step in, and what role do they play?

As mentioned earlier, these top models combined with mainstream Vibe Coding tools already surpass most senior engineers in many ways. This isn’t just about fewer bugs, but also about finding issues during reviews that humans might miss—AI really does read code line by line.

So what role do humans play in this process, and which stages still require humans?

First, obviously, humans define the requirements. Only you know what you actually want. That sounds simple, but in practice it’s often hard to describe your needs precisely at the beginning. I sometimes use a lazy trick: role-playing with AI. For example, when developing the PostgreSQL version of TiDB, I asked the AI to pretend it was a senior Postgres user and tell me which features are critical, must-have, and high-ROI from a developer’s perspective. It then generates a list of features based on its understanding, and you refine that list together. This is a very efficient cold-start method.

Second, after requirements are proposed, most coding agents go through a planning phase and repeatedly confirm details with you. There are some tricks here. For example, don’t give the AI overly specific solutions—let it propose solutions and focus yourself on the desired outcome. Also, tell it about infrastructure and environment constraints early so it doesn’t waste time.

I also usually require the agent to do certain things right from the start. For example, no matter what task it’s working on, it must put plans and to-do lists into files like work.md or todo.md. After completing each phase, it should update lessons learned in agents.md. And once a plan is completed and the code is merged, the design document should be added to the project knowledge base (.codex/knowledge). I include all of this when I first state the requirements.

The next phase is long investigation, research, and analysis. Humans basically don’t need to do anything here, and agents are far more efficient than people. You just wait. The only thing I pay attention to is telling the model that it has unlimited budget and time, and should research as thoroughly as possible. If the model has reasoning-depth settings, I recommend setting them all to xhigh at this stage. It’s slower, but spending more tokens here leads to better planning and understanding, which helps a lot later.

The implementation phase doesn’t have much to say. I basically don’t read AI-generated code line by line anymore. The main rule I follow is: either let AI do everything, or do everything yourself—never mix the two. In my experience, zero human intervention during implementation works better.

The fourth phase is where humans become very important: testing and acceptance. Personally, about 90% of my time and energy with AI projects goes into this phase—evaluating results. In Vibe Coding, my rule is: “There’s a test, there’s a feature.” If you know how to evaluate and test what you want, AI can build it.

AI will automatically add many unit tests, and at a micro level those usually pass. But AI is weak at integration tests and end-to-end tests. For example, in a SQL database, each unit test might pass, but integration tests can still fail. So before reaching big milestones, I always work with AI to build a convenient integration testing framework and prepare testing infrastructure early. I also collect and generate ready-to-run integration test cases, ideally with one-click execution. Instructions for using this testing infrastructure are written into agents.md upfront, so I don’t have to explain it repeatedly.

As for where tests come from: you can ask AI to generate them, but you must specify the logic, standards, and goals. And never mix the test-generation context with the main development agent’s context.

The fifth phase is refactoring and decomposition. I’ve found that when a single module exceeds around 50,000 lines, current coding agents struggle to solve things in a single shot. On the flip side, this means that below that complexity threshold, many tasks really can be done in one shot with a good first prompt. Agents also don’t proactively manage project structure or module boundaries. If you ask them to implement a feature, they’ll happily dump everything into a few massive files. It looks fast in the short term, but it creates massive technical debt.

At this stage, I usually stop, use my own experience to split modules, and then do one or two refactoring rounds under the new architecture. After that, high-parallel development becomes possible again.

Some practices around multi-agent collaboration

As mentioned earlier, I rarely use just one coding agent. My workflow usually involves multiple agents working. That’s why I sometimes spend thousands of dollars on a project—you need real concurrency. But beyond throughput, having agents review each other’s work without shared context significantly improves quality. It’s like in team management: you don’t let the same person be both athlete and referee.

For example, one workflow I use a lot is this: first, use GPT-5.2 in Codex to generate design documents and detailed plans for multiple features, and save all those planning docs. Then, still in Codex, implement features one by one based on those documents. During implementation, I track to-dos and lessons learned. Before committing, I stop and hand the working directory to another agent—Claude Code or OpenCode—without context, and ask it to review the uncommitted code and suggest changes based on the design. I then send those suggestions back to Codex, let Codex evaluate them and apply changes if they make sense. After that, Claude Code (Opus 4.5) reviews again. Once both sides are satisfied, I commit the code, update the knowledge base, mark the task complete, and move on.

In large projects, I also run multiple agents in parallel (in different tmux sessions), each responsible for completely different modules. For example, one modifies kernel code, another works on frontend UI. If multiple unrelated changes are needed in the same codebase, you can use git worktrees so agents work on different branches independently, which boosts throughput.

The future shape of software companies and organizations

What will future software companies look like? From my own practice and conversations with friends, one thing is clear: token consumption across a team follows a classic 80/20 distribution. The top engineers who use AI best may consume more tokens than the remaining 80% combined. And the productivity gain from coding agents varies wildly between individuals. For the best users, it might be 10x; for average users, maybe only 10%.

The main bottlenecks become human code review and some non-automatable production operations (though those may not last long). This allows top engineers, with AI assistance, to work without clear boundaries. More and more “one-man armies” will appear. For now, capability is strongly correlated with token spend: how many tokens you can burn roughly reflects how much you can achieve.

Another interesting observation: even among 10x engineers, their Vibe Coding workflows and best practices differ significantly. This means two top Vibe Coders are actually very hard to collaborate within the same module. It’s more like a head wolf leading a pack of agents in its own territory. One territory doesn’t easily accommodate two head wolves—otherwise you get 1 + 1 < 2.

In this organizational model, traditional “team collaboration” gets redefined. We used to emphasize many people working closely in the same codebase and module, aligning through reviews and discussions. In Vibe Engineering, a more effective approach may be strongly decoupled parallelism. Managers should split problems into clear, well-defined “territories,” and let each top engineer lead their agent pack to optimize locally.

From a management perspective, this is a big challenge. You can’t enforce uniform processes and rhythms anymore. For top Vibe Coders, too much process and synchronization actually kills efficiency and cancels out AI gains. Management becomes more about resource scheduling and conflict isolation—minimizing interference between head wolves while enabling collaboration through clear interfaces, contracts, and tests when needed.

Because of all this, AI-native R&D organizations are very hard to grow bottom-up from non-AI-native ones. Most developers’ first reaction to change is avoidance or resistance, not embracing it. But progress doesn’t stop for individual preferences. There’s only proactive adoption or passive adoption.

I’ll stop here. Overall, in this environment, individuals face a profound transformation. As I mentioned in a WeChat post last week, some of the best engineers around me are experiencing varying degrees of existential crisis. As a builder, I’m excited—creating things now has much lower barriers. If you can find meaning and fulfillment in building, congratulations: you’re living in the best era.

But as a human in the abstract sense, I’m pessimistic. Is humanity ready for tools like this, and for the societal and civilizational impact they bring?

I don’t know.